Between 1776 and 1875, the Portuguese Empire shifts its main axis of intervention from Brazilian

territories to Africa, aiming to strengthen territorial occupation and resolve the complicated

issue of slavery. According to most historiography, with the Brazilian cycle closed and despite the

successive reforms, the empire fell into a relative lethargy. However, it is precisely during this

period that we find an increasing concern by the authorities in calculate and control the population.

This effort came through and producedseveral hundreds of statistical

maps covering irregularly the various territories. Population statistics were a key instrument

in the construction of States and modern forms of colonialism. Knowledge and quantification

reinforced the control over territories and populations and led to new policies. The long process

of creating a legal framework and a bureaucratic apparatus, able to produce, collect and interpret

the numbers, allowed a first quantification and classification of overseas populations.

The statistics, its categories and production circuits demonstrate the intensity with which the

State grasped its territories and began building a new order. On one hand, the acquired knowledge

enabled the creation of models for occupation and classification of the territory. On the other,

it shaped the way these territories were perceived and how people imagine themselves.

For the Portuguese, the existence of a significant corpus of population

statistics available for the overseas empire, since mid-18th century has been generally disregarded

by historians and demographers. This project represents the first attempt to gather, process and

analyse the “statistical maps” enacted by royal order and to create reasonably reliable demographic

series and indicators for each of the Empire’s territories.

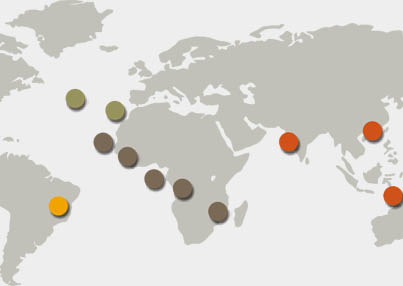

For this purpose, we will study the demographic tendencies for each

territory: Brazil (1776-1822), Azores and Madeira (1776-1834), Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, São

Tomé and Príncipe, Angola, Mozambique, Portuguese India, Macau (1776-1910) and Timor (1850-1875).

Depending on the available information, we will quantify: i) annual growth rates, territorial

division and urbanisation levels; ii) population structures (socio-professional, religious and

ethnic distribution, active population and age composition); iii) demographic behaviours (fertility,

mortality and migration balances).

In addition to the strictly demographic analysis, the project also

encompasses the study of the reasons that led the Crown and the Liberal State to order this

extensive set of maps. Thus, we may provide new data for the analysis of several policies tied to

Empire: territorial occupation, population management, taxation, conscription and the use of labour

force.

What would the population of the Portuguese Empire have been in 1800 or 1850? How many

Europeans were there in Angola, or in Goa? Where was the enslaved population percentage higher?

This research aims to quantify and analyze the living conditions of the various ethnic,

religious, free, and non-free groups that existed in the Portuguese Empire.

The Counting Colonial Populations’ project goes far beyond numbers and quantification.

It aims to uncover new

What would the population of the Portuguese Empire have been in 1800 or 1850? How many

Europeans were there in Angola, or in Goa? Where was the enslaved population percentage higher?

This research aims to quantify and analyze the living conditions of the various ethnic,

religious, free, and non-free groups that existed in the Portuguese Empire.

The Counting Colonial Populations’ project goes far beyond numbers and quantification.

It aims to uncover new